If you want to order this book send us an e-mail (info@afdh.nl)

with your adress specifications.

We will send you the book as soon as possible with an apropriate invoice.£ 30 (England)

$ 60 (USA)

€ 34,50 (Netherlands, Belgium,

Germany, France)

(shipping costs included)334 pagina's | 334 pages

gebonden | bound in cloth

volledig in kleur | full colour

met cd-rom | with cd-rom

Engels | Englishisbn 9789072603401

Catalogue

A look insideFamous and infamous:

the story of an eighteenth-century Dutch publisherThe Leiden bookseller and publisher Elie Luzac (1721-1796) had a vast European network. The way in which Luzac operated in this network of professional relationships sheds illuminating light on the international book trade of the eighteenth century. Elie Luzac (1721-1796). Bookseller of the Enlightenment is a work that puts developments in today’s publishing world in a new perspective. Book historian Rietje van Vliet’s awardwinning biography of the single-minded publisher Luzac is now available in an English translation for non-Dutch historians, bibliophiles and readers with a marked interest in the Enlightenment.

Elie Luzac has been awarded his rightful place in a most impressive way. [...] The reader learns a lot about the European, specifically Dutch book trade, about Luzac’s own company, his business strategies, his political views and the relationship between publishers and authors.

Dr. Roelof van Gelder, NRC HandelsbladIn her lucidly written book-historical study which bears witness to an impressive erudition, Rietje van Vliet’s chief focus of interest is to reconstruct the nature of Luzac’s publishing business. [...] The work offers the reader a fascinating and broad panorama of the book trade and its functions in

eighteenth-century Dutch society.

Prof. dr. Wyger R.E. Velema, BMGN – Low Countries Historical Review'Mrs Van Vliet’s study is exemplary of the new approach to book history.’

Jury report Menno Hertzberger Prize, 13 November 2009.

‘Elie Luzac:

the last major Dutch publisher with a European outlook’Rietje van Vliet received her doctorate presenting a biography of the Leiden bookseller and publisher Elie Luzac (1721-1796) some years ago. As an independent researcher she publishes regularly on various aspects of the Dutch book trade in the early modern period. Her biography won the prestigious Menno Hertzberger Prize: ‘an excellent example of the modern approach to book history’. The English-language edition of her book has now been published by afdh Publishers.

Elie Luzac (1721-1796). Bookseller of the Enlightenment is a thorough book historical study of well over 330 pages. However, an interview with Rietje van Vliet (1954) on the subject of her study never gets bogged down in academic jargon. She talks about Luzac, his business and his times with lively enthusiasm. ‘He was forever reading and entering | into debates but he also cut a great figure on the dance floor and on the ice rink.’ She laughs as she recalls how one of the reviewers of her book objected to her use of the word ‘love child’. ‘It’s a very nice word and it’s obvious what is meant’, says van Vliet, ‘and after all, it really was Luzac’s love child. So why would a word like that have no right to appear in a dissertation?’

An enlightened conservative

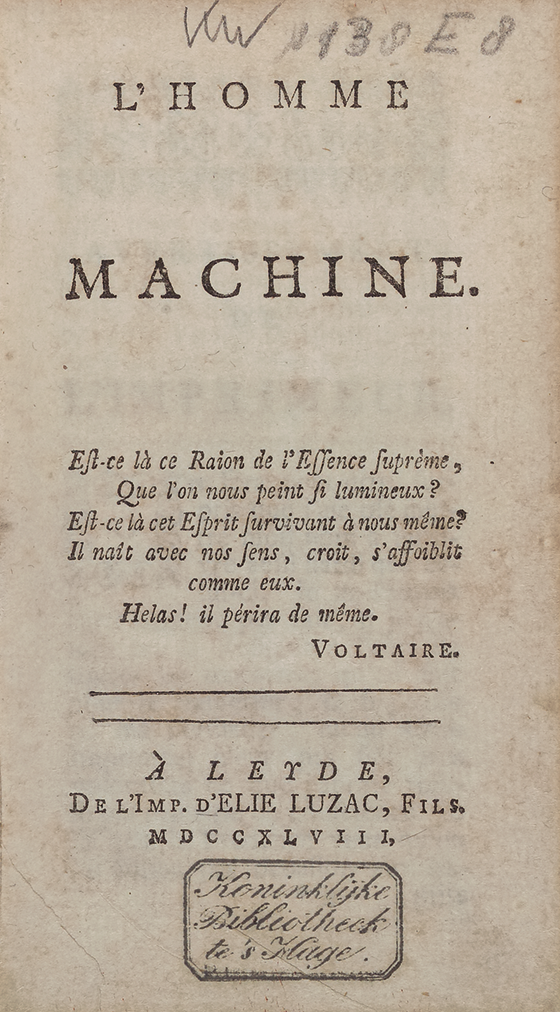

Elie Luzac published more than 200,000 pages in print. When he brought out the highly inflammatory L’Homme Machine, it was out of deep conviction but also with a keen sense of profit. The work was subsequently burnt, and its publisher put on trial. Luzac was eventually fined 2,000 guilders, the equivalent of 35,000 Euro. In other books, Luzac confronted Rousseau with a heated polemic. To the last of his life, he defended the claims of the House of Orange, in a climate of mounting patriotism, in the Dutch Republic. By all rights he can be called an enlightened conservative bookseller and a philosophe. Van Vliet’s book is a passionate story about Elie Luzac’s life and the place of the Dutch book trade in the national and European context in the years 1750-1800.Networker

‘Dutch publishers were able to dominate the European book markets for decades on end’, Rietje van Vliet says. This was already the case in the seventeenth century. In the following century too the sky seemed to be the limit when it came to the foreign market. The Dutch became ‘the brokers of our ideas’, as Luzac wrote in his Hollands rijkdom. He himself was convinced that conditions in the Dutch Republic were ideal for the role the book trade had to play; there were many internationally acclaimed scholars working in the Republic, the quality of the printing was high and the prices relatively low, and there was freedom of the press. Luzac was a highly successful networker, especially in such countries as Germany and France, and his business thrived as a result.

This flourishing situation in the Republic changed around 1760, van Vliet remarks, when Dutch publishers began to lose their competitive edge in the West-European book trade. Instead, they began to focus on the domestic market. ‘This is also clear from what Luzac published in those days. From that time on, he mostly brought out works dealing with strictly national issues. He never stopped publishing books that expressed his political republican ideals, or works on freedom of thinking and acting. But towards the end of his life, the spirit of the time had caught up with him.’The publisher as a peer reviewer

No academic writer can survive without a publisher, now as much as in Luzac’s time. He was known and celebrated as a scholarly publisher and everybody wanted to be published by him. ‘Luzac was a sharp thinker and debater, as appears from his correspondence with a man like Jean Henri Formey, the learned secretary of the Academy of Sciences in Berlin. Luzac read all his manuscripts, and he also reviewed and edited them for Formey. As an editor he was as imperious as he felt was necessary. A peer reviewer avant la lettre, I suppose you might call him.’No author’s rights but copyright

Still a young man, Luzac already ran a publishing, printing and bookselling firm on Leiden’s highly exclusive Rapenburg. From there he built up a vast network that came to include almost every Enlightenment author who meant anything. Van Vliet: ‘They liked to have him

as their publisher, even if he put a pirated edition of their work on the market. There was no such thing as author’s rights, even though a publisher could lay claim to some form of copyright. Beyond provincial or national borders, books were, you might say, a free-for-all commodity, and anyone could pirate them. It was a lucrative trade for the publisher, but the customers also benefited, because pirated editions kept prices sharp.’

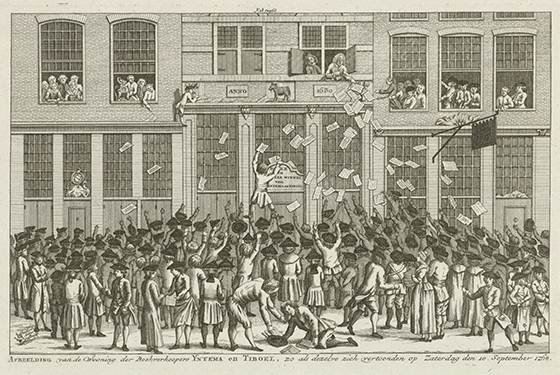

Luzac’s own publishing list also includes pirated editions. He was quick to cash in, for instance on a blazing row between his friend Samuel König and the uncrowned Berlin bully Maupertuis about the latter’s unashamed plagiary of Leibniz: ‘The Leiden publisher brought out a volley of König’s accusatory essays and Voltaire’s malicious attacks, but he also printed pirated editions of the work of Maupertuis. Three men who would happily drink each other’s blood, forced to coexist on one and the same publisher’s list.’Luzac’s shop in Leiden was never pillaged, but his Amsterdam colleagues Yntema and Tieboel were not so lucky. The illustration shows an enraged public turning against these two hapless publishers of anti-Orangist pamphlets (1768). In the 1780s, however, it was the patriots’ turn to visit Luzac. His shop was commonly known as the place in town for political works and Orangist printing. Luzac’s political opponents tarred the front of his shop. Luzac himself was hated, even molested, because of his outspoken views.

Learning from Luzac

Luzac himself authored a large number of the works on his list. ‘He was very strong analytically and verbally. An opinion-maker with a single mission, which was to prove that the Republic was a hundred times better off with a hereditary stadtholder than with the Regents’ faction in power.’ Van Vliet hesitates which opinion-maker today compares with Luzac. Al Gore or Joschka Fischer? Guy Verhofstadt? ‘Luzac has a pungent style of writing. His work is proof of his great erudition. It’s often impossible to contradict. Many of his contemporaries hated him for it, because he just wasn’t prepared to compromise or give in. He was simply always right and never wrong.’ He was just as headstrong as a publisher and bookseller. ‘Publishers nowadays can learn a thing or two from Luzac: you need to invest in your authors, you need to look beyond national borders and you need to network. He did all of that and he did it extremely well’, van Vliet thinks. He also teaches you to be accurate when editing and printing works. ‘Sloppy printing won’t get you anywhere, and the same goes for poorly edited texts. You can only become a quality publisher with a list to match when you stick to your

chosen policy and demand the best from your editors and designers. Luzac also had a feeling for that aspect of book production: the aesthetically pleasing combination of text and image. He commissioned the famous Amsterdam engraver Jan Punt to cut new plates for the fables of Jean de la Fontaine, for instance, rather than rely on older illustrations, which would have been a lot cheaper.’Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the Dutch market began to change. A great many translations became available, especially from the German, mass literature was on the rise and novels were published in large editions. ‘By that time’, Rietje van Vliet says, ‘the curtain had already fallen for Luzac.’

Dr. Rietje van Vliet is an independent researcher. She investigates various aspects of the book trade history in the 17th-18th centuries. Elie Luzac (1721-1796) is her thesis (2005).

Rietje van Vliet was awarded the Menno Hertzbergerprice in 2009. This price (since 1963) is an award for researchers who contribute significantly in the field of the bookscience and bookhistory. Elie Luzac (1721-1796) is a fine example.